Patrick Condon’s study of Vancouver and other rapidly growing cities shows that adding density does not ease escalating housing costs, but does just the opposite, by driving up land values

‘Land Crush’ is the headline of a new Triangle real estate industry report. It describes Raleigh’s red-hot investor bidding wars and illustrates the central message of a new book by Patrick Condon: that adding density does not ease escalating housing costs, but does just the opposite, by driving up land values. Patrick Condon is Vancouver’s award-winning emeritus city planner and professor of sustainable urban growth. His new book is Sick City: Disease, Race, Inequality, and Urban Land.

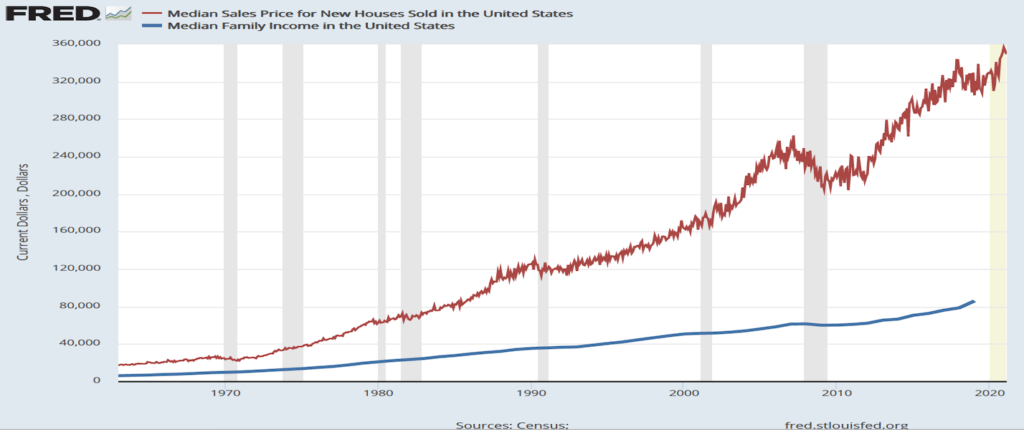

Condon’s study of Vancouver and other rapidly growing cities shows that the widening gap between housing costs and most incomes is caused by escalating land prices, not construction costs or zoning rules. Condon quotes the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas: “Land prices, not construction costs, hold the key to understanding the trajectory of house prices in the long run.“ He also notes that the City of Houston, which is famous for operating without zoning controls, has seen a 27% increase in average home prices over 5 years, despite an inflation rate of less than 2%.

The widening gap between Family Incomes and Home Costs

While upzoning land for more density drives up land values and costs, making all housing more expensive, upzoning in older, affordable neighborhoods is especially destructive to community life when cities fail to counter upzoning’s gentrifying impacts:

-

-

- escalating taxes

- fines

- dislocation

- eviction

- demolition

-

Declining opportunities to build wealth in homeownership are often viewed as a consequence of ingrained race disparities, but Condon details how the economic outlook for others is also bleak:

Younger American Whites now find themselves facing similar financial stresses as their African-American peers. Millennial-generation Whites are now also virtually closed out of the opportunity to build [home ownership] wealth enjoyed by many of their parents. [In cities like Boston] today’s average wage earner would need 22 years to save enough money for a 20 percent down payment on a decent home. For Baby Boomers, it took only five.

Condon describes Vancouver’s rapid growth in the 1980s and 90s: “Faith in ‘supply and demand’ was very strong, and the argument was made by almost everyone that the answer to the problem of affordable housing was more supply. [The] presumption was that there would be some kind of trickle-down—that, even if the new supply was aimed at the high end of the market, benefits would accrue to the lower end of the market by freeing up housing units. After many years of pursuing this strategy, it turned out that this was not the case.” As a result, Vancouver’s mayor is taking action:

It is no longer adequate to assume that adding supply is going to solve the housing affordability crisis. [In the future,] the approach will be to enthusiastically support only supply that is aimed at the people who live in Vancouver and make average incomes – specifically, housing that can be afforded with 30-35 percent of the average income of workers in the city.

Vancouver

For years, Condon led Vancouver’s much-admired sustainable growth revolution by promoting high quality urban amenities in exchange for very high densities. Vancouver’s formula for success has been widely emulated, but in cities less confident about their attractiveness to investments, high quality community benefits are left out. That’s good for investor profits, but bad for a city.

A recent example is Raleigh’s rush to approve the record-setting 40 story upzoning at Downtown South without corresponding record-setting community benefits such as affordable housing. According to Condon, the unfortunate and foreseeable effect of Council’s unilateral gift of 40 story land value is this: It will further accelerate Raleigh’s Land Crush for investor profits and, in turn, accelerate the rising cost of housing for everyone.

In the closing chapters of his book, Condon studies how cities have been working, with widely varying degrees of success, to increase their supplies of affordable housing, concluding that unless escalating land costs are brought under control, with that value redirected to productive uses, our efforts will increasingly be in vain:

As a city makes progress, adding jobs and skilled labor, all of that creative energy gets inexorably vacuumed into land price, up to and beyond the point where lowest-wage workers live a precarious existence where one life tragedy puts them on the street: poverty.

In a follow up blog we will look at some of the tools Condon has studied for increasing the supply of affordable housing, applying them to Raleigh’s Land Crush and growing affordable housing crisis.